"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

02/24/2014 at 10:10 • Filed to: planelopnik

17

17

48

48

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

02/24/2014 at 10:10 • Filed to: planelopnik |  17 17

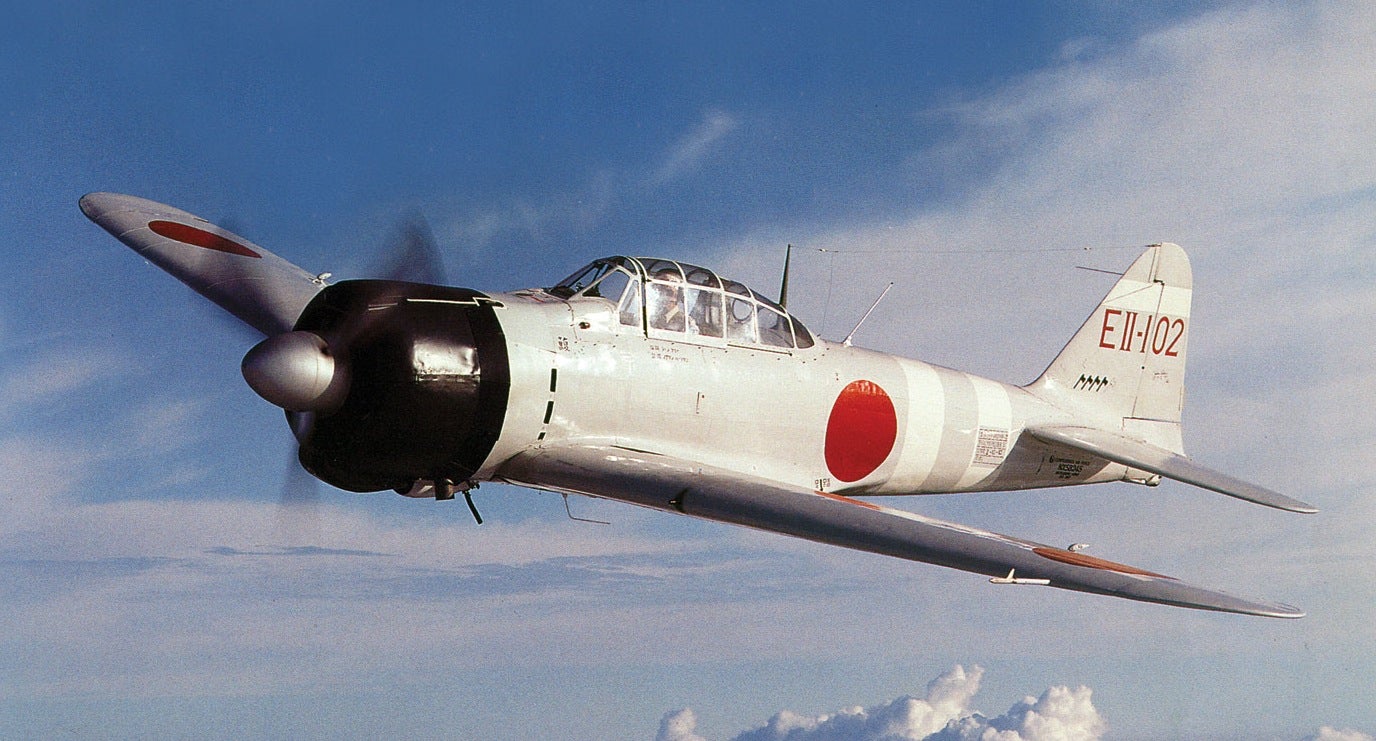

|  48 48 |

In the early days of WWII, the Japanese Zero fighter, which was more maneuverable than anything the Allies could field at the time, ruled the skies over the Pacific. In one battle in April of 1942, 36 Zeros attacked the British naval base at Columbo, Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka). About 60 RAF aircraft rose to meet them, a mix of different types, many obsolete. After the battle, almost half of the RAF planes were shot down: 15 Hawker Hurricanes, 8 Fairey Swordfish, and 4 Fairey Fulmars. The Japanese lost 1 Zero. [1] Early in the war, the Zero enjoyed a 12-1 kill ratio. [2]

Allied commanders knew that their planes were no match for the Zero. So they needed to devise a way to beat a superior plane by using superior tactics. One of the first to work out a way to deal with the Zero was Claire Chennault, commander of the famous Flying Tigers. Officially called the !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! (AVG), the Flying Tigers were an assortment of pilots who volunteered to fight for China against the Japanese invasion. The best fighter they could get at the time was the !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! . While it was no match for the Zero in a head-to-head fight, Chennault taught his men how to be successful with the less maneuverable Warhawk.

Edward Jablonski, in his excellent history of WWII aviation Airwar , writes:

Chennault stressed the excellent flying qualities of the Japanese pilots, although emphasizing their tendency to fly mechanically and employ a set tactical routine. Chennault also introduced the Americans to the Zero fighter, indicating its strong points as compared with the P-40: higher ceiling, superior maneuverability, and better climbing ability. But, Chennault also pointed out, the P-40 was a more rugged aircraft, could take more punishment, and, thanks to self-sealing fuel tanks, was not so readily combustible. The P-40 was also equipped with armor plate, which the Zero lacked, thanks to the Japanese pilots’ insistence on high maneuverability. Also, the heavier P-40 could outlive (that is to say, outrun) the Zero. “Use your speed and diving power to make a pass, shoot and break away.”

In other words, dive, shoot and run. Don’t stick around to fight, because you’ll likely get shot down.

The United States was drawn fully into the Pacific War after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and in the first months its pilots were hard pressed to deal with the superior Zero fighter. But then, they caught a break.

Concurrent with the

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

in early June of 1942, the Japanese occupied the islands of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians, perhaps hoping to divert attention away from their real target, Midway Island (if it was indeed a feint, Admiral Nimitz never took the bait). On June 4, 1942, before Japanese troops moved in, a group of Japanese planes took off from the carrier

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

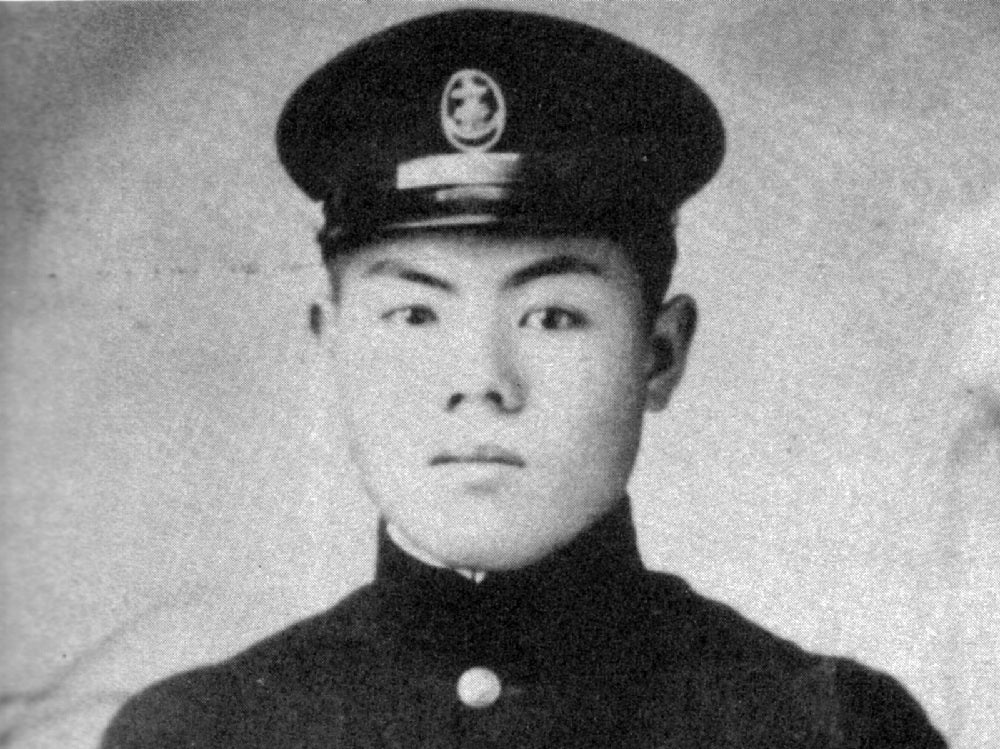

to bomb Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians. After the attack, Flight Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga, flying an A6M2 Zero, noticed that he had been hit by ground fire and was losing fuel. He knew he would not be able to return to the Ryujo.

Flight Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga [3]

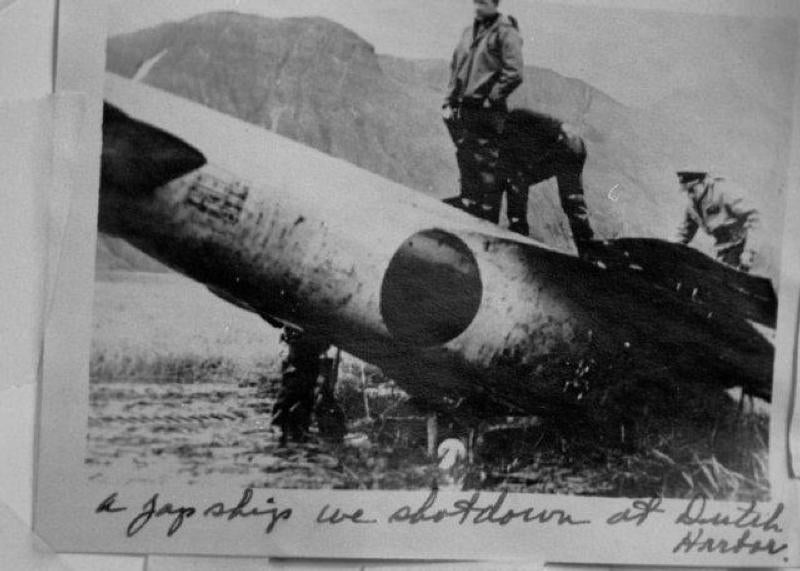

Koga radioed to his flight leader that he would land at one of two islands designated for emergency landings and await rescue by a Japanese submarine. Koga chose Akutan Island. His wingmen surveyed the landing area, and they thought a safe landing could be accomplished. Koga touched down, but the aircraft immediately flipped on its back. The ground that looked solid from the air turned out to be soft, wet tundra.

Koga’s Zero, as the Americans found it on Akutan

Standard procedure dictated that the other pilots should destroy the downed Zero to keep it from falling into enemy hands. But Koga’s comrades thought there was a chance that he was still alive. They couldn’t bring themselves to strafe their fellow pilot. What they didn’t know was that Koga died instantly when the plane flipped over. The other pilots returned to the carrier, not realizing that they were leaving behind a nearly intact aircraft.

Five weeks later, the overturned Zero was spotted by a Navy reconnaissance plane and a salvage operation was undertaken. US Navy personnel made their way to the plane and found the lifeless Koga still hanging upside down in the cockpit. They buried his body, and the plane was shipped intact (the construction of the Zero prohibited the removal of the wings) to Naval Air Station, North Island, San Diego where it was repaired. Flight testing began immediately.

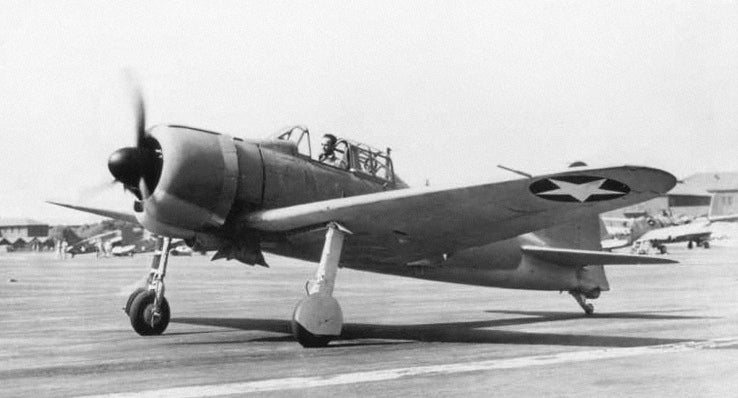

The very first flight exposed weaknesses of the Zero that our pilots could exploit with proper tactics. The Zero had superior maneuverability only at the lower speeds used in dogfighting, with short turning radius and excellent aileron control at very low speeds. However, immediately apparent was the fact that the ailerons froze up at speeds above two hundred knots, so that rolling maneuvers at those speeds were slow and required much force on the control stick. It rolled to the left much easier than to the right. Also, its engine cut out under negative acceleration (as when nosing into a dive) due to its float-type carburetor. [4]

The Akutan Zero in American markings undergoing testing at North Island [5]

The Navy, and later the Army, pitted the captured Zero against the best fighters of the day: the P-38 Lightning, the P-39 Airacobra, the P-51 Mustang, the F4F-4 Wildcat, the F4U Corsair. Lt. Cmdr. Eddie R. Sanders made twenty-four flights in the captured Zero on September and October of 1942.

“We now had an answer for our pilots who were unable to escape a pursuing Zero. We told them to go into a vertical power dive, using negative acceleration, if possible, to open the range quickly and gain advantageous speed while the Zero’s engine was stopped. At about two hundred knots, we instructed them to roll hard right before the Zero pilot could get his sights lined up. This recommended tactic was radioed to the fleet after my first flight of Koga’s plane, and soon the welcome answer came back: It works!” Sanders said, satisfaction sounding in his voice even after nearly half a century. [6]

It has been said that the design of the !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! , which Grumman developed as a replacement to the F4F Wildcat, was influenced directly by the discovery of the Akutan Zero. However, the recovery of the crashed Zero came much too late in the Hellcat’s development process to affect its design. The first flight of the Hellcat came in October of 1942, only one month after the Akutan Zero began flight testing in the US. By then, the Hellcat was well on its way to production, though it didn’t reach the fleet until August of 1943. [7]

As for the plane itself, it was destroyed during a training accident in February of 1945 when an SB2C Helldiver lost control while taxiing and rammed into it, slicing the plane to bits with its propeller. Several gauges were salvaged and donated to the National Museum of the US Navy, and other small pieces now reside in the Alaska Heritage Museum and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. [8]

Sources:

Airwar

, by Edward Jablonski (Doubleday, 1971)

[1, 4, 6]

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

[2, 3, 5, 8]

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

[7]

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

Jayhawk Jake

> ttyymmnn

Jayhawk Jake

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 10:20 |

|

Great article.

It always disappoints me that the Zero is associated with Kamikazee, in the sense that many people assume it was a bad airplane flown by bad pilots whose only goal was to kill themselves in combat.

That's just not true, it was an impressively capable fighter flown by fairly talented pilots that presented a legitimate and formidable threat to American fighters in the early days of the war. It and it's pilots weren't bad, the Americans were just better .

JR1

> ttyymmnn

JR1

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 10:25 |

|

Great article, I remember watching something about this event on Pawn Stars once. This crash was a huge victory for the allies, and they didn't even have to do anything! Rebuild a Zero and then build a better plane from its remains. Quite lucky if you ask me!

spanfucker retire bitch

> ttyymmnn

spanfucker retire bitch

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 10:25 |

|

Ahh The Zero. The very definition of a Glass Cannon. Or perhaps Paper Cannon would be more apt?

I loved watching all the documentaries they used to air on the History Channel (before they stopped covering History) about all the most famous planes used during WWII. It was fascinating to see just how each nation prioritized the capabilities of their aircraft. I don't think there was ever a bigger dichotomy than the U.S. and Japan during the early days of the Pacific War. One side with an absolute zealous attitude toward lightness and maneuverability and the other with much heavier armor to better protect the plane and pilot.

Fascinating stuff. Thanks for posting.

spanfucker retire bitch

> Jayhawk Jake

spanfucker retire bitch

> Jayhawk Jake

02/24/2014 at 10:27 |

|

Well, it's mostly true that the pilots who were performing the Kamikazee attacks were bad. Because at that point in the war, the Japanese had suffered such heavy losses they could no longer field a full crop of trained pilots with veteran instructors.

bimmerismyname

> ttyymmnn

bimmerismyname

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 10:28 |

|

Nice write up. I'm a WWII buff myself. Enjoyed this very much

ttyymmnn

> Jayhawk Jake

ttyymmnn

> Jayhawk Jake

02/24/2014 at 10:29 |

|

Thanks.

I think folks tend not to look at the whole picture. As you say, the Zero was an excellent plane and its pilots were, at first, world class. By the time the Japanese got to the point of turning Zeros into human-guided bombs, the war was lost for them, the Zero was mostly obsolete, and most of their good pilots were dead. They just couldn't keep up with the production and technological development of the US. The US also had the distinct advantage of not having its factories and cities being bombed into oblivion. Yamamoto knew what he was up against:

If it is necessary to fight, in the first six month to a year of war against the United States and England I will run wild. I will show you an uninterrupted succession of victories. But I must also tell you that if the war be prolonged for two or three years I have no confidence in our ultimate victory.

ttyymmnn

> spanfucker retire bitch

ttyymmnn

> spanfucker retire bitch

02/24/2014 at 10:34 |

|

Definitely, the American emphasis was on survivablilty, for both the plane and the pilot. The Japanese emphasis was on maneuverability. The pilot was not the priority, but I wonder if that is an outgrowth of a society where harakiri was a common practice. Giving your life for your emperor was encouraged. But as Patton said, "No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. You won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country."

Krieger (@FSKrieger22)

> ttyymmnn

Krieger (@FSKrieger22)

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 10:45 |

|

Great writeup on it, even if I've heard the tale before. Are you planning a writeup on Arnim Faber's Fw 190 sometime?

By the way, just what happened to the Akutan Zero after the war? I've heard that it's still around, but it was only from one source and I couldn't quite confirm it at the time.

ttyymmnn

> Krieger (@FSKrieger22)

ttyymmnn

> Krieger (@FSKrieger22)

02/24/2014 at 10:51 |

|

Two excellent questions. A write up on Faber's 190 is a great idea for an article. As for the Akutan Zero, it was destroyed in a ground collision with a Helldiver while taxiing. Wikipedia has the story:

The Akutan Zero was destroyed during a training accident in February 1945. While the Zero was taxiing for a take-off, a SB2C Helldiver lost control and rammed into it. The Helldiver's propeller sliced the Zero into pieces. From the wreckage, William N. Leonard salvaged several gauges, which he donated to the National Museum of the United States Navy. The Alaska Heritage Museum and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum also have small pieces of the Zero.

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 11:21 |

|

ttyymmnn

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

ttyymmnn

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

02/24/2014 at 11:26 |

|

Fascinating picture. I've never seen that one before. That's Akagi , right?

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 11:28 |

|

Since living in Japan I have been looking into various subjects here. The Alaskan island occupation is interesting.

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 11:29 |

|

Yes its a very rare picture, and it is in fact the Akagi. I like the shot of the chrysanthemum on the bow.

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> spanfucker retire bitch

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> spanfucker retire bitch

02/24/2014 at 11:32 |

|

Not really bad, often 15 years old and little training. The Germans ran out of good pilots as well and many of the kills were due to them not having learned very much.

spanfucker retire bitch

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

spanfucker retire bitch

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

02/24/2014 at 11:34 |

|

I don't know about you, but that fits my definition of the word "bad." They had just about enough training to learn how to fly and land the plane before they were sent to a carrier group - only then to be encouraged to fly into a U.S. naval ship.

ttyymmnn

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

ttyymmnn

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

02/24/2014 at 11:35 |

|

Rare indeed. I've seen thousands of photos of WWII, particularly aviation photos, as it's one of my hobbies, and I've never seen that picture. Thanks for sharing. I tried to work in that third photo of the US personnel climbing on the Zero, but couldn't manage it. There are others of that scene, including pictures of Koga's body. I felt no need to post that photograph.

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 11:43 |

|

I think I found it on a Japanese site, I get my wife to help me with searches sometimes because we don't get access searching in English. I really looked into the Alaskan period a few years ago, I came across some interesting stuff I didn't know about. I was alive in Europe during the war and I never thought about all this going on elsewhere.

f86sabre

> ttyymmnn

f86sabre

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 11:47 |

|

Great piece. Nice to combine the technical with the personal story.

The antagonists testing each other's planes leads to all kind interesting tales. This was just an extension of espionage that was practiced on a number of levels. The Zero was a feared mystery to a lot of airmen. I imagine that getting those tips was a great relief.

Kugelblitz

> ttyymmnn

Kugelblitz

> ttyymmnn

02/24/2014 at 12:44 |

|

Harakiri had nothing to do with it. Japanese martial traditions emphasize precise maneuvering to deliver a lethal strike at the optimal moment and range. The Zero emphasized that. Even Japanese medieval armors reflected this, movement and flexibility were hallmarks for them.

The later fighter aircraft produced by Japan were plagued by mechanical problems but the Raiden or the A6M5 were pretty deadly as well, they just didn't have the numbers or training by then. The pilots that did survive were still very lethal people to dogfight with. Saburo Sakai was one of many.

f86sabre

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

f86sabre

> Gimmi-Sagan-Om-Draken

02/24/2014 at 22:46 |

|

What did you look into? My father-in-law has been working on a book about Attu Island during the war for a while. I'm not sure how serious he is about it anymore. He is visiting this weekend and I will need to ask him about it.

hismiths

> ttyymmnn

hismiths

> ttyymmnn

02/27/2014 at 20:19 |

|

The company the built the Zero makes a nice car now ... Fuji Heavy Ind./Subaru.

Hawkstrike6

> Kugelblitz

Hawkstrike6

> Kugelblitz

02/27/2014 at 20:37 |

|

Yeah, the Zero's design is very much influenced by the philosophy of war outlined in The Book of Five Rings.

But the Japanese had fantastic pilots at the start of the war, too — their loss doomed the Japanese Navy, as even as hard pressed for materiel as Japan was, it was easier to replace airplanes than combat-experienced pilots.

KirkyV

> hismiths

KirkyV

> hismiths

02/27/2014 at 20:40 |

|

I thought the Zero was a Mitsubishi?

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

02/27/2014 at 20:48 |

|

Same as the U.S. logically than aye ?

KayGB

> ttyymmnn

KayGB

> ttyymmnn

02/27/2014 at 21:24 |

|

In an ominous foreshadowing of the future, during the combat flight tests against 6 or so Allied fighters, the Zero was the only aircraft that made it through the duration of the test without requiring repairs, other than normal servicing.

KayGB

> KirkyV

KayGB

> KirkyV

02/27/2014 at 21:29 |

|

Fuji evolved from Nakajima, makers of the Rufe floatplane, basically a Zero as a floatplane

KayGB

> KirkyV

KayGB

> KirkyV

02/27/2014 at 21:34 |

|

In fact, It looks like there are 4 Rufes moored (or adrift) in the aerial photo provided by Gimmi.

KirkyV

> KayGB

KirkyV

> KayGB

02/27/2014 at 21:37 |

|

I don't claim to be an expert on the subject by any means, but I was under the impression that the Rufe was a development of the Zero, not the other way around?

Hondanazi

> KirkyV

Hondanazi

> KirkyV

02/27/2014 at 21:46 |

|

It was made by Mitsubishi it was called A6M

McPherson

> ttyymmnn

McPherson

> ttyymmnn

02/27/2014 at 22:34 |

|

Great story, thanks. Hayao Miyazaki's fictionalized tale of aircraft designer Jiro Horikoshi, 'The Wind Rises', gets wide US release tomorrow, 28 Feb.

ttyymmnn

> McPherson

ttyymmnn

> McPherson

02/27/2014 at 22:39 |

|

Thanks. I just saw an ad for that film for the first time yesterday. I will definitely check it out.

Maxaxle

> ttyymmnn

Maxaxle

> ttyymmnn

02/27/2014 at 22:40 |

|

You call this "touched down"?

McPherson

> ttyymmnn

McPherson

> ttyymmnn

02/27/2014 at 22:45 |

|

It's very good from what I've heard, a must see. Keep those great articles coming.

merlyn11a

> ttyymmnn

merlyn11a

> ttyymmnn

02/27/2014 at 22:59 |

|

A commonly unmentioned issue with Zero-sen fighters (and other non-US/UK a/c) is the failure of communications. Radios were notoriously poor in Zeros and quite often, the pilots had them removed in order to reduce weight. This affected all sorts of tactics, whether offensive or defensive, and dictated, unfortunately for the Japanese pilots, the number of choices they could use when engaging in shotai (roughtly 3 plane element), chutai (3 shotais), or sentai (3 shotais) tactics. The rough equivalents would be like a 2 or 4 plane fighter element/rotte, a schwarm or flight. But, imagine, being in a squadron formation about to attack a similar formation of enemy a/c and being totally unable to talk to your element leader or wingman while in the midst of maneuvering for advantage. Or being in the same scenario defensively, with no way to warn a compatriot about to be in trouble or even call for help when under attack. This is a rarely mentioned critical problem with IJN and IJAAF Zeros; most people talk about non-sealing fuel tanks or the poor damage survivability and they forget to mention about fighter pilots being able to talk to each other about what is going on and what is about to happen. Essentially, it relegated the Japanese pilots to fight in a WW1 style maneuvering style versus a combined element(s) team style fight. Good radios are/were a critical element in combat and should not be ignored. Imagine being in a modern F1 car where you could have equivalent engine/transmission technology but half the teams were not allowed to have any data or voice transmissions from their cars. It would be very interesting to see......but it wouldn't be hard to predict what would happen.

Also, the article briefly mentions Claire Chennault but doesn't mention that he had been sending information about the Nate and Zero back to the US as early as 1939 and 1940 respectively. However, US aviation "experts" claimed that the Japanese were not capable of building such aircraft. When the Zero information was sent back to the US, it was entirely disregarded and never passed on. Thus, when 7 Dec. '41 occurred, US pilots were in for a rude surprise.

ttyymmnn

> merlyn11a

ttyymmnn

> merlyn11a

02/27/2014 at 23:31 |

|

Terrific information. Thanks.

Weather and Darkness

> McPherson

Weather and Darkness

> McPherson

02/27/2014 at 23:44 |

|

I heard about this very film on these very pages only a little while ago. I thought it came out ages ago. Didn't realize it was as recent as this.

gmporschenut also a fan of hondas

> ttyymmnn

gmporschenut also a fan of hondas

> ttyymmnn

02/28/2014 at 00:00 |

|

Bombing of Japan didn't begin until June of 44, same time as the famous Marianas Turkey Shoot. Their factories were perfectly fine before then.

OttoMaddox

> ttyymmnn

OttoMaddox

> ttyymmnn

02/28/2014 at 01:38 |

|

Great article, but I must clear up one misconception. The Zero did not operate in the China Burma India Theater in 1940-41 so Chennault's AVG did not encounter any. They did face the Nakajima Ki 43 Hayabusa (Oscar) which looked similar and was also highly maneuverable. They quickly learned to use their P40's strengths and fly around their shortcomings and many Wildcat pilots applied those lessons when the US officially entered the war.

merlyn11a

> OttoMaddox

merlyn11a

> OttoMaddox

02/28/2014 at 01:49 |

|

Hmm, respectfully must disagree.

Per Wiki :

The first Zeros (pre-series A6M2) went into operation in July 1940. [13] On 13 September 1940, the Zeros scored their first air-to-air victories when 13 A6M2s led by Lieutenant Saburo Shindo attacked 27 Soviet-built Polikarpov I-15s and I-16s of the Chinese Nationalist Air Force, shooting down all the fighters without loss to themselves. By the time they were redeployed a year later, the Zeros had shot down 99 Chinese aircraft

and :

One Mitsubishi A6M2 Navy Type 0 Carrier Fighter, Model 11 s/n 3372 originally marked " V-172 " and belonging to the " Tainan Kokutai ", part of " 22nd Koku Sentai "; piloted by Tainan buntaicho Lt. Kikuichi Inano , departed from Tainan airfield ( Taiwan ) en route to Saigon ( French Indochina ) and crashed in Leichou Pantao (also known as Leizhou or Luichow Peninsula), near the town of Qian Shan ( Teitsan ), China . The pilot was captured by Chinese forces on November 26, 1941. The aircraft was later sent by AVG to United States was the very first intact Japanese A6M fighter captured as a prize of war, also known as the " Mystery Zero ", " China Zero " or " Tiger Zeke " [

In addition, per this interesting page : war prizes

merlyn11a

> ttyymmnn

merlyn11a

> ttyymmnn

02/28/2014 at 02:06 |

|

Great article; have to say also, there is a huge amount of misinformation out there about Zeros and how the US found out about them. For sure, Claire Chennault, undersung and unappreciated US fighter pilot theoretician and practical applicant, supplied plenty of information to the US mainland about Japanese advances. But US prejudicies and biases prevented these reports from being fully utilized.

However, it is also true that the AVG, composed of USN, Marine, and USAAC "volunteers", learned very well from Chennault who had years of experience flying in China against the Japanese; his lessons were gleaned from his own pre-war ideas of fighter operations (and which earned him enmity and exile from the wrathful USAAC which really was in love with the idea of strategic bombardment) and practical operations in China with various mercenaries and a mélange of Western and Russian aircraft. Operating against the Japanese with the polyglot of Western merc pilots and hodgepodge of mediocre aircraft honed his ability to make the best of what he had on hand.

You can find various pubs where very early in the war and even pre-war, unblooded USN and Marine pilots discuss via grapevine about rumors of "hot" Japanese planes and how some people in China had figured out ways to counter them. So it appears through classic scuttlebutt, some information made its way to the right people. But, still, it's not quite the same as an official tactical bulletin (of which there soon came to be many) and again, OEMs didn't get the word in a timely fashion (although it might be said that they wouldn't have paid it much heed anyways).

SquirrelyWrath

> ttyymmnn

SquirrelyWrath

> ttyymmnn

02/28/2014 at 05:48 |

|

Japans undoing was to keep experienced pilots on the front lines instead of retiring them back to flight schools to train the next generation. Heavy losses therefore created a talent drain they could not recover from. Germany suffered a similar loss of experienced pilots when the luftwaffe was largely destroyed. They both also insisted on sacrificing large portions of what was left of their fighting forces in futile gestures instead of resorting to a more asymmetric tactic of hit and run. But even that couldn't have granted them victory. Simply more favorable terms of surrender. To many mistakes were made before then.

spanfucker retire bitch

> Reckoning Day

spanfucker retire bitch

> Reckoning Day

02/28/2014 at 07:07 |

|

Nay. The U.S. did not suffer the same "brain drain" effects as the Japanese pilots did near the end of the war. We weren't forced to send our trainers into battle because they were our last crop of veteran pilots. We weren't having our training bases bombed on a nearly daily basis. We also had a much larger population pool to pull from.

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

02/28/2014 at 20:54 |

|

Thanks for the info.. I am Canadian so out of the US loop...

..there must have been at least SOME effect to EVERY country participating though I would suspect...

Tell me the effects on this issue with the US as it is a very interesting topic to me....

spanfucker retire bitch

> Reckoning Day

spanfucker retire bitch

> Reckoning Day

02/28/2014 at 23:10 |

|

The effect on the U.S. was that we turned into a Super Power.

I mean, every country was negatively affected by the war. We lost hundreds of thousands of men during the course of it. However with the exception of Pearl Harbor (and some uninhabited Alaska Islands) we we were never attacked on our own soil. So our entire national industry was put toward the war effort.

Instead of making cars, trucks and commercial planes, industrial plants all around the U.S. were diverted to make fighters, bombers, battleships, carriers, tanks. Other factories were re-purposed for other purposes obviously. Everything from bullet and explosive manufacturing to the textiles industry for pumping out uniforms. There were massive shortages of resources for the civilians during the war as all resources were diverted toward the war effort. Rubber (again, for civilians) was in especially short supply.

Pretty much the entirety of our national economy was put toward the war effort, and since none of our factories or cities were ever struck, we got out of the war pretty much unharmed with the exception of the casualties our soldiers suffered in Europe and the Pacific.

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

03/01/2014 at 19:47 |

|

Yep that part I remember, well done.

What about the issue of at least some very experienced US pilots killed and how well the ones who replaced them did or did not do in comparison ?

I suspect the US trained all very well, but I could be wrong. Did some youngish hotshots die too? being too possibly cocky and inexperienced ?

...Or are we not to know that information ?

spanfucker retire bitch

> Reckoning Day

spanfucker retire bitch

> Reckoning Day

03/01/2014 at 22:33 |

|

Well I don't know that specific information. Perhaps Google could help you. Ever nation lost talented individuals and knowledge - the U.S. was just the least affected of them.

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

Reckoning Day

> spanfucker retire bitch

03/02/2014 at 22:15 |

|

Yes I agree with you & that was my initial point....

Bob1931

> ttyymmnn

Bob1931

> ttyymmnn

05/23/2016 at 22:46 |

|

Grumman data lists the first flight of the F6F as 06/26/1942 with Bob Hall at the controls.